Recently, there has been a surge of demand for street food — which is most often categorized as an informal cuisine — in many metropolitan areas around the world, including New York, Los Angeles and Shanghai. In fact, it becomes highly reassuring to see that the underdog street cuisine can survive, perhaps even compete, in the ruthless urban jungles, each armed with its own abundant shares of lavish brick-and-mortar restaurants, serving up “proper” food on a white, glistening platter.

It is not until one completely immerses oneself in the asphalt sprawl of cheap eats that the cemented boundary between meals prepared with stainless steel pans and wooden skewers begin to dissolve. This line becomes blurred by not only eating these quick bites, but also personally engaging with the vendor, who stands a couple of feet in front, preparing one’s meal within his or her view. How is this food perceived? Can cheaper ingredients thrown together with cheaper utensils be acknowledged as “proper” cooking? Does “proper” food only occur within building walls? Can street vendors can be considered both laborers and artists?

Captivated by their tasks, we wanted to know more about how street vendors learned their trades. When asking the vendors about how long it took for them to learn the process of making their food, we got a range of answers. While some only took about a week to learn the basics, from procuring ingredients to the ins and outs of the cooking process, others said it took them months — even years — to perfect their trade.

One man from Henan province described his art of making shuǐjiǎo 水饺, a variation of jiɑ̌ozi 饺子, which literally means “water dumpling.” Shuǐjiǎo are small boiled dumplings typically filled with ground pork and scallions. “It takes time,” Zhēn Yòu 真佑 described, recalling how he moved from his home province 22 years ago with his sister. While he knew how to make the dumplings before, Zhēn Yòu had to adapt his process after he decided to purchase a mobile metal card to start selling them on the street. Now in 2016, he and his wife have adapted team approach to making these small treats.

“Now I don’t have to think about it. My hands move and my eyes don’t have to follow.”

Zhēn Yòu and his wife making shuǐjiǎo

Their approach almost mimics an assembly line — together they are a well oiled machine with a little more flare. Each dumpling is hand rolled and folded, giving each one a unique shape, and the filling is limited to their imagination.

Street food vendors spent years doing the same seemingly monotonous movement over and over. They spend hours prepping and cooking their signature dishes, just as a painter spends hours preparing the paint and planning the strokes of his brush. Additionally, the vendor’s completed dish, parallels that of a painter’s finished work, both pieces subject to evaluation, appreciation, and critique from an audience. Simply, the vendor’s signature dish transcends the basic demands of nourishment and becomes an art form of itself.

Potters and weavers were the first models of craftsmanship who were able to distinguish their profession from unskilled manual labour. As communities enlarged, more diverse artisans such as wheelwrights, blacksmiths, and stonemasons emerged. In fact, these specialized laborers and predecessors were the primary producers of consumer products and final goods until the Industrial Revolution. Within the scope of Karl Marx’s historical materialism, the unified associations of these variously skilled tradesmen, or simply guilds, actually comprised the predominant economic regime between the transient eras of feudalistic agriculture and industrial capitalism. Today, artisanal works — although the terminology is routinely perverted by marketing schemes to conjure images of production exempt of machinery — attempt to preserve and even retard the invasive and standardized practices of modern industry. Clearly, it is fitting to regard artisans and craftsmen as highly essential components of not only economic activities in the past, but also the preservation of creative design today.

Arguably, cooking and preparing foods vastly supersedes any other artisanal forms such as wheel-making and watchmaking in terms of prevalence, recognition, and everyday use. To narrow down even further, it is important to acknowledge the craftsmanship and artisanal flair involved in street food. This deceptively simple craft involves a multitude of skills. Flour pounding, dough rolling, and flap pinching for the wonton — all executed with impressive precision and speed — are a common sight while walking the streets of Shanghai.

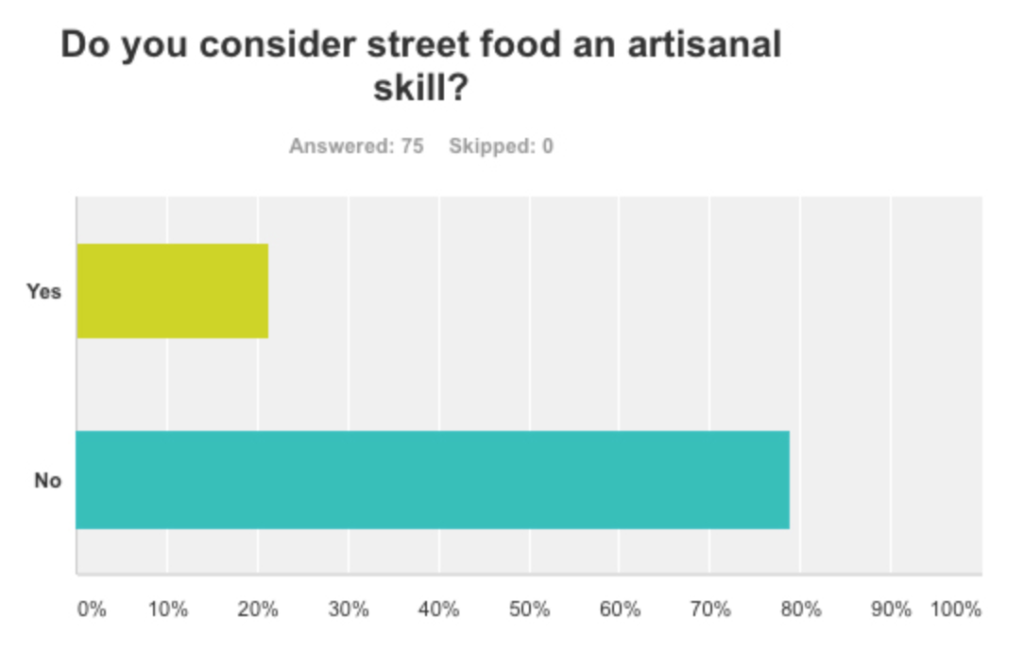

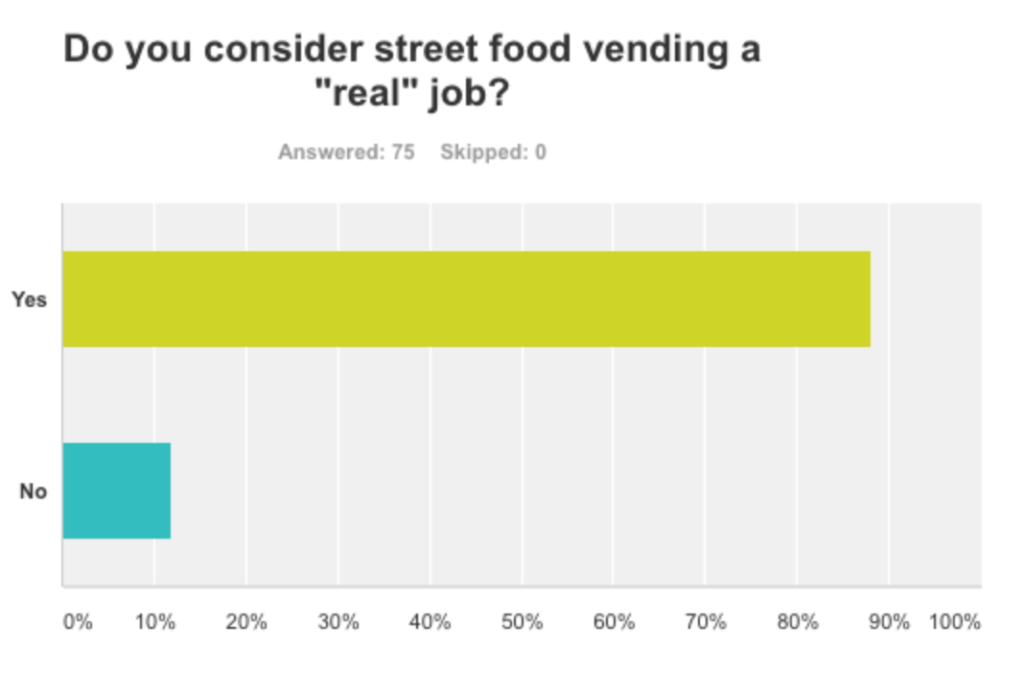

That said, although the preparation and cooking of street food thoroughly embody the qualities of an artisanal skill, a majority of public opinion teeters away from the appreciation of this handmade cuisine. In order to get more information, we surveyed 75 current NYU Shanghai students about their opinions on street food. The questions were aimed to assess the current social atmosphere surrounding around street food.

When we asked students if they considered street food vending to be a “real” job, 88% of students thought yes. While it was clear that the majority of NYU students viewed street food vending as a legitimate occupation, when asked if they considered making street food an artisanal skill about 79% responded no.

There seems to be a clear disconnect in public opinion. We believe this disconnect could be due to one key reason.

There seems to be a clear disconnect in public opinion. We believe this disconnect could be due to one key reason.

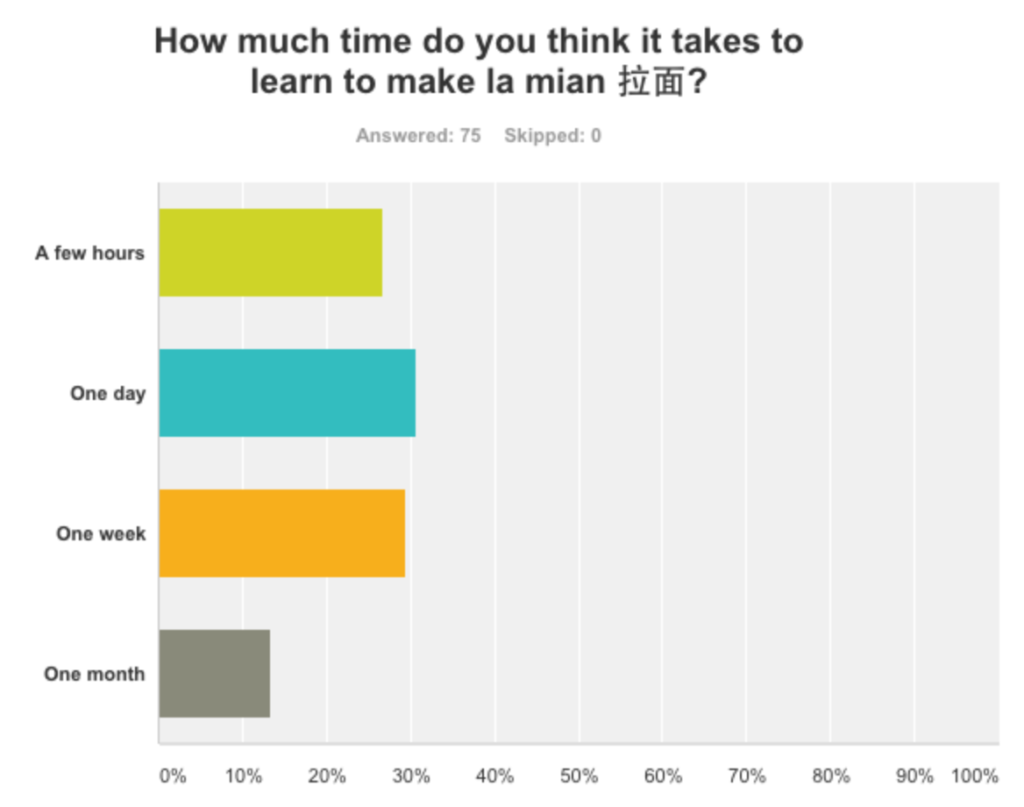

The student population is unaware of the skill needed to make these foods. When we asked if students would be able to prepare a popular noodle dish known as lāmiàn 拉面 many students answered “yes.” Additionally, when we asked how long students thought it took to learn how to make lāmiàn 拉面, we got a range of answers ranging from one day to one month. Some even said a few hours.

The process of making lāmiàn 拉面 by hand is extremely complex and requires a lot of skill. After finding the correct dough to water ratio, one must stretch the dough into noodles — which is not an easy task. By repeatedly pulling and twisting the dough onto itself, making sure the thinning fibers don’t snap, one slowly forms the characteristic thin strands of lāmiàn. Despite his extensive culinary training, even the professional chef Gordon Ramsay fails miserably when trying noodle pulling for the first time. Even a professional chef couldn’t learn to make lāmiàn in a few hours! When Ramsay asked the chef how long it will take to be as good as him, he bluntly replies “ten years!”

The process of making lāmiàn 拉面 by hand is extremely complex and requires a lot of skill. After finding the correct dough to water ratio, one must stretch the dough into noodles — which is not an easy task. By repeatedly pulling and twisting the dough onto itself, making sure the thinning fibers don’t snap, one slowly forms the characteristic thin strands of lāmiàn. Despite his extensive culinary training, even the professional chef Gordon Ramsay fails miserably when trying noodle pulling for the first time. Even a professional chef couldn’t learn to make lāmiàn in a few hours! When Ramsay asked the chef how long it will take to be as good as him, he bluntly replies “ten years!”

He becomes an appendage of the machine, and it is only the most simple, most monotonous, and most easily acquired knack, that is required of him.

— Karl Marx

By1911, the onslaught of Modern Industry was fully underway in Europe and the United States. Crude production of coal, steel, and oil dominated manufacturing powerhouses and mass migrations from the rural fields began to storm the urban centers. Most importantly, the factors of production now not only required manual labor but also utilized heavy machinery as well. In an attempt to further labor productivity and economic efficiency, mechanical engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor stressed overturning the empirical “rule of thumb” school of thought — the prevalent, if not the standard, protocol by the late 19th century — by applying instead, the scientific method. Outlined in the The Principles of Scientific Management (1911), his revolutionary theories in industrial engineering can be easily condensed into these four points:

- Replace rule-of-thumb work methods with methods based on a scientific study of the tasks

- Scientifically select, train, and develop each employee rather than passively leaving them to train themselves

- Provide “Detailed instruction and supervision of each worker in the performance of that worker’s discrete task”

- Divide work nearly equally between managers and workers, so that the managers apply scientific management principles to planning the work and the workers actually perform the tasks

Simply, implementation of meticulous and precise calculations, derived from the time and motion studies done by Taylor, usurped the use of practical and subjective judgement. Furthermore, task allocation, or the subdivision of labor, demanded that achievement of a goal, such as the completion of a product, be broken down into smaller and smaller tasks. This maximization of work fragmentation allowed the minimization of required skills and time for labor. Illustrated by the rise of vertically and horizontally integrated conglomerate giants in the 20th century, such as Monsanto and Tyson, Taylorism has become indispensable to providing goods at an unprecedented rate while truncating costs. Specifically, considering the dominance of pre-packaged store bought foods, the assembly line approach is increasingly becoming the status quo for how the products that we consume are made. Yet, the sacrifice for efficiency is more than alarming: the human element — ranging from mismatched girth of wontons to hearty comfort food made with love — has been compromised.

3 street vendors make Ugyhur flat bread (nan) with an assembly line method

Amidst today’s frenzy of consumerism and homogenized production, street food represents one of the final frontiers of artisan cooking. Street craftsmen in Shanghai churn out dishes by hand with exceptional skill and practice. Yet, even at this elementary scale of food production, Taylorism is evident. Through the combined efforts of husband and wife, hand cut noodles, dumplings, and nan breads are rapidly made in an assembly line fashion. While commonly perceived as a perfunctory, inferior job, making street food is crucial to preserving a culinary art which demands high level of expertise.

Learning to stretch noodles or roll dough like a street food vendor takes time, just like learning the piano. Without hands-on practice, a beginner lacks the artistry and finesse. One needs time and practice in order to perfect a skill — and this is supported by neuroscience!

Neuroscience has evolved from the study of simple behaviors to examinations of complex behaviors, including elaborate motor tasks such as kicking a ball or playing the piano. The learning process necessary for stretching noodles or rolling dough would be considered a sensorimotor task. This means it involves our sensory pathway of our central nervous system, how we touch and feel the outside world, as well as our motor pathway, which controls how we move our bodies.

There are three stages of motor learning: the cognitive stage, the associative stage, and the autonomous stage. The cognitive stage is the initial stage of learning where one gets an overall understanding of the skill. This stage mainly relies on the learner’s visual input as they must really pay attention to the actions they are making in order to grasp how to generate the necessary motions. The next stage is the associative stage, where one has had some practice and shows greater refinement of the skill. In this stage there is more emphasis on proprioceptive cues, where one feels where one’s body is in space, rather than visual cues. The final stage is the autonomous stage. It takes time to get to this stage, as your brain needs time to “rewire” and form these new motor associations. In this stage, the motor skill is mostly automatic and requires little cognitive involvement. You can think of a professional pianist — they don’t have to think about how their fingers are moving over the keys, they keep their eyes on their sheet music and let their fingers follow — just like Zhēn Yòu when making shuǐjiǎo and this champion noodle puller blindfolded!

Conclusions

By attributing unskilled manual labour to this trade, fellow students and city dwellers alike solely reap the benefits of street food’s convenience and affordability, yet dismiss the craftsmanship and human touch involved in creating each vendor’s art form. In fact, because brush is to knife as canvas is to chopping board, it is only sensible to argue that informal cooking is entirely an individualistic process. And, because individualism and ingenuity heavily reside in the food making process, street cooking, while maintaining time and movement efficiency, must persist to combat the encroachment of the standardized industrial process. By recognizing the artistic element evident in street food, we can help keep this art alive by supporting people, not machines.